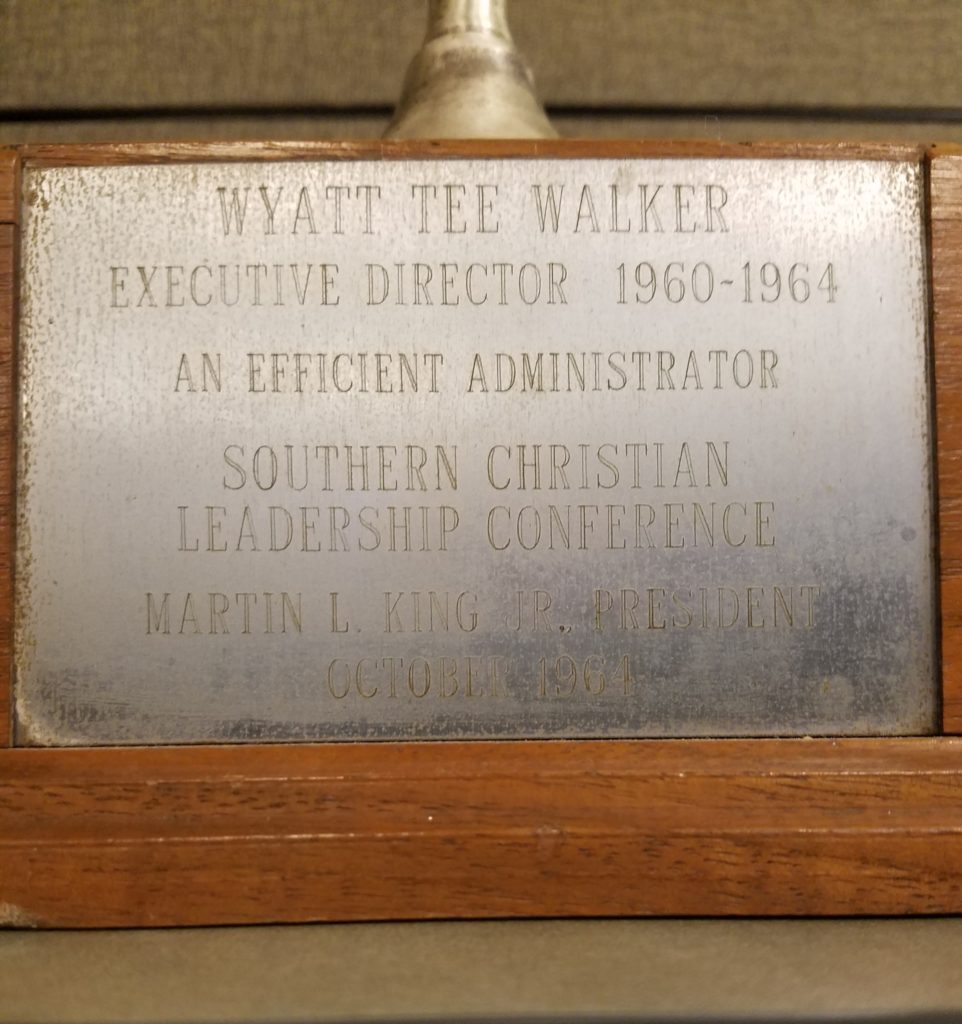

(Note: This post was authored by Taylor McNeilly, Processing & Reference Archivist.) Happy #WyattWalkerWednesday, and welcome to another post on the Something Uncommon blog. This week, I’d like to take the opportunity to discuss a question some of our readers have asked me about the audio cassette tapes in the Dr. and Mrs. Wyatt Tee Walker Collection. I’ll give a bit of background to the question and then we’ll dive right in!

Some of you have picked up on how often I discuss the preservation of physical materials, including the longevity of certain formats. I’ve mentioned in previous blog posts, for instance, that audio cassette tapes are generally expected to hold their recording for 20-50 years, depending on how often they are played and the environment they’re stored in. This was part of the reason we digitized the cassette tapes as quickly as we did: many of them are well past that initial 20 years, so we knew we could be losing data every minute we waited.

This brings us to the question some of our readers have asked: how long will the digital formats last? Will we be back here in 20 years changing the format of these recordings to avoid data loss? The Walker collection will certainly still be here in 20 years, and it is the duty of archivists everywhere to think about the long term (think “forever”), so how long will digitized material last?

Data loss in the digital world is colloquially known as bit rot, and it’s actually much closer to how cassette tapes lose data than you might guess. Hard drives and cassette tapes record data in similar but different ways: both use magnetic charges to store the data, but how they use the charges is different. Hard drives use a positive or negative magnetic charge to store data in binary, the coding language that is the basis for all computer work. As you might guess from the name, binary has two “letters” in the language: 1 and 0. Using positive and negative charges for the 1 and 0, computers magnetically store information on hard drives. Every file on every computer is a series of 1s and 0s strung together, much the way that a cassette tape is a series of magnetic data stored along the magnetic tape itself.

Since both formats store data magnetically, data loss is surprisingly similar: the storage medium, whether it be the magnetic tape in a cassette or the hard drive of a computer, loses that charge – or switches it. With a cassette tape, there’s not much you can do about this except copy it onto a new tape before it starts to happen, thereby restarting that 20-year countdown to data loss. An archives would maintain an appropriate storage environment for cassettes, extending that 20 years as long as possible, but eventually the physical preservation would require what archivists called migration. Migration can occur from one physical format to another, called format migration (such as from a wax cylinder to a vinyl LP to a cassette), or it can be a migration from one instance of a format to another instance of the same format (an old cassette to a new cassette). There is a lot of discussion in the archives profession about format migration and the loss of contextual information (what does it tell you about a recording that it is on vinyl instead of a cassette, and how do we ensure that information is included if we change formats?), but format migration is recognized as necessary to preserve material indefinitely.

You may recall that I’ve mentioned that the Birmingham Campaign recordings we have were recorded onto cassette in the early ’90s, so this material had actually undergone one migration before they came into our possession (and were also 25+ years old). Since audio cassettes weren’t commercially available in the U.S. in 1963, I can be fairly confident in calling this a format migration – probably from audio reel to cassette tape, although we can’t be certain without doing some investigation.

With computers, the answer isn’t much different – but it is much easier. If you’ve ever moved a file from one computer to another, or uploaded it into the cloud, or sent it in an email to yourself or someone else, then you might have performed a basic function of digital preservation. Data migration is obviously much easier on a computer than a cassette – all you have to do is copy and paste the file, and you’ve created a new, second copy. Many computers have the ability to hold multiple hard drives, so as one hard drive ages a newer one can be installed and the files can be copied over, ensuring that the information is safe.

To make copying a file actual preservation, you need to do more than just put it on a new hard drive. Digital archivists function under a basic principle, called LOCKSS. LOCKSS stands for Lots Of Copies Keep Stuff Safe. Essentially, if you have three or more copies, you can be certain that bit rot won’t get all of them – and if it does, it won’t get all of them at the same time, allowing you to make three new copies of whichever version survived. Once cloud services became a thing in the 2000s, LOCKSS became very easy to handle: just keep a file on your hard drive and upload another copy onto a cloud service.

Some cloud services take an extra step, backing up data in the cloud to three servers. Some go even further, checking the files periodically to ensure that none of them have suffered bit rot. If one version of a file has been damaged, it can be restored using the other two. Cloud services that perform this sort of automated maintenance on files are very helpful for archives, assuring that digitized material will survive as long as the service is available. So to answer the question “how long will the digitized versions of the cassette tapes last,” I can confidently say “for the foreseeable future.”

Things get much more complicated than just ensuring a file’s integrity using LOCKSS, including different ways to verify a file’s integrity. There are also concerns about file format obsolescence, and because of this digital format migration is also a practice in archives. I can address these questions at a later date, but for now we can all rest easy knowing that, by being digitized and properly safeguarded, the Birmingham mass meetings and other recordings will be safely preserved and accessible well into the future.

As always, thanks for checking in on the Dr. and Mrs. Wyatt Tee Walker Collection this #WyattWalkerWednesday. Feel free to ask any questions or leave any comments you have, and follow Boatwright Library’s other social media, including Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.