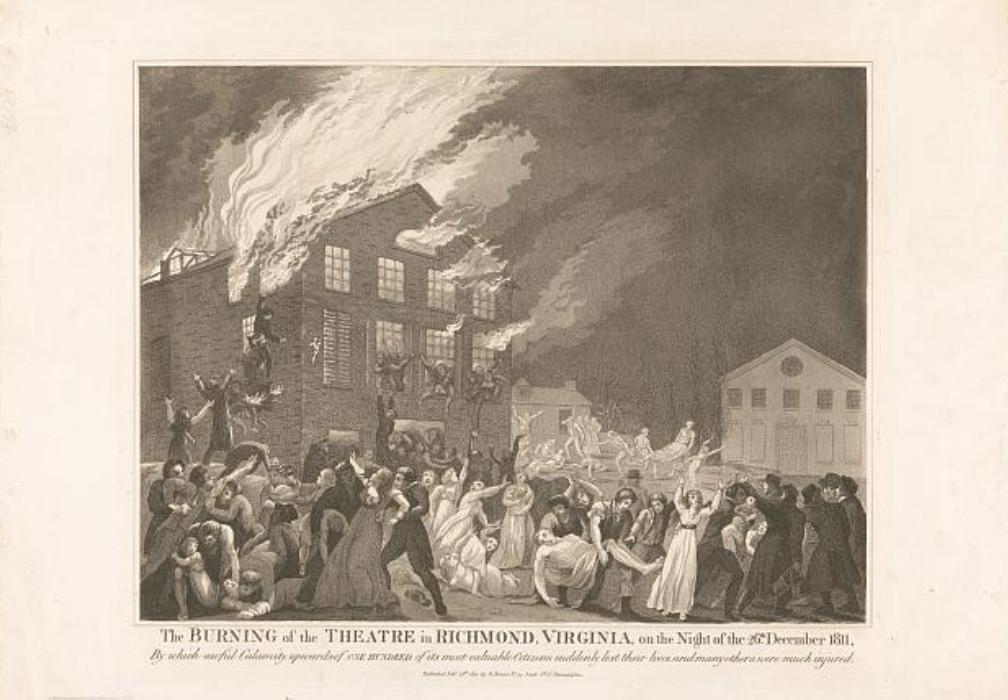

On December 26th, 1811, several hundred Richmonders gathered together at the Richmond Theater to enjoy a night of drama, but the drama that unfolded was not a part of the play’s script. As the oil lamp chandelier was raised into the rafters for the show to begin, it caught the pine wood ceiling, the thick, heavy curtains, and the painted set pieces on fire. The building was consumed by flames, and those inside were desperate to get out. The individuals sitting in the galley and the pit of the building, where the seats were the cheapest, were the first to escape. The entrances and exits were close to these seats, unlike those in the boxes on the second floor. The box seats were expensive, and many of the most influential people in Richmond at the time were seated here. The box seats were reached by long, narrow passageways. Unfortunately, these seats were difficult to escape from in an emergency situation. The fire became so severe that people on the second floor were jumping from windows in order to survive the fire at any cost. The chaos of the evening made it incredibly difficult to figure out who was still inside the theater and how to get them out. Once the embers subsided, a panicked inquiry regarding the causes and casualties of the fire began in Richmond.

The burning of the theatre in Richmond, Virginia, on the night of the 26th. December. , . [No Date Recorded on Shelflist Card] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2003689321/

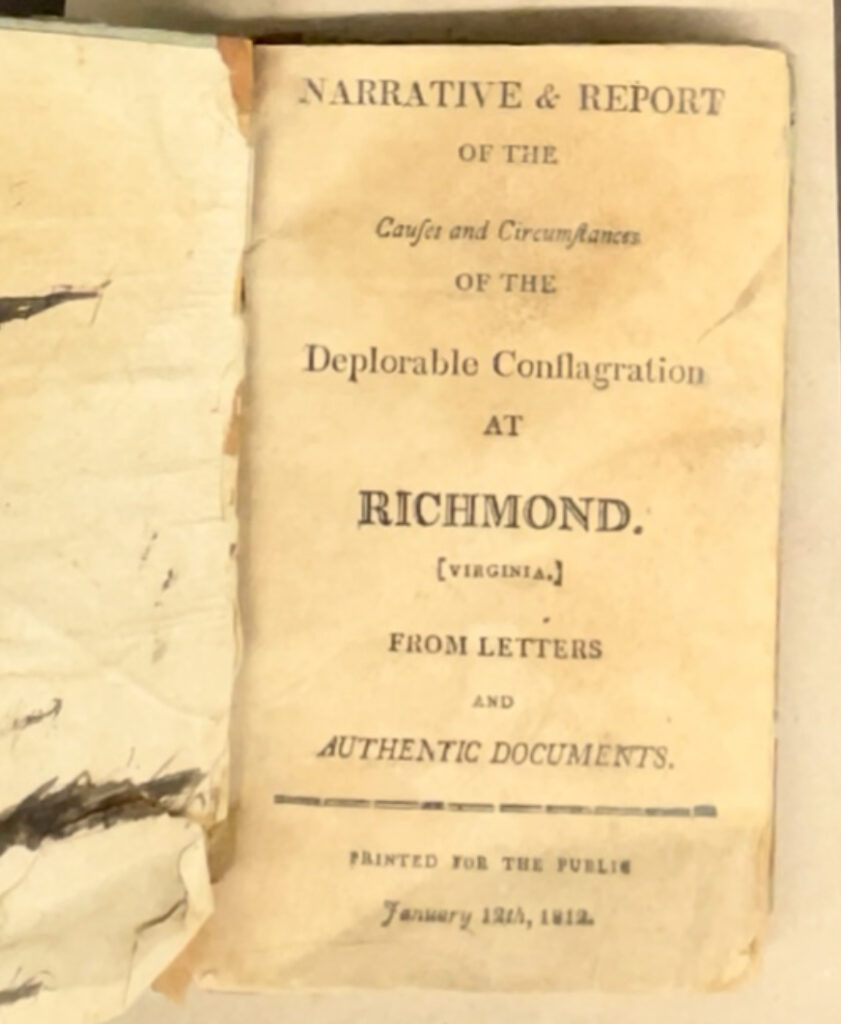

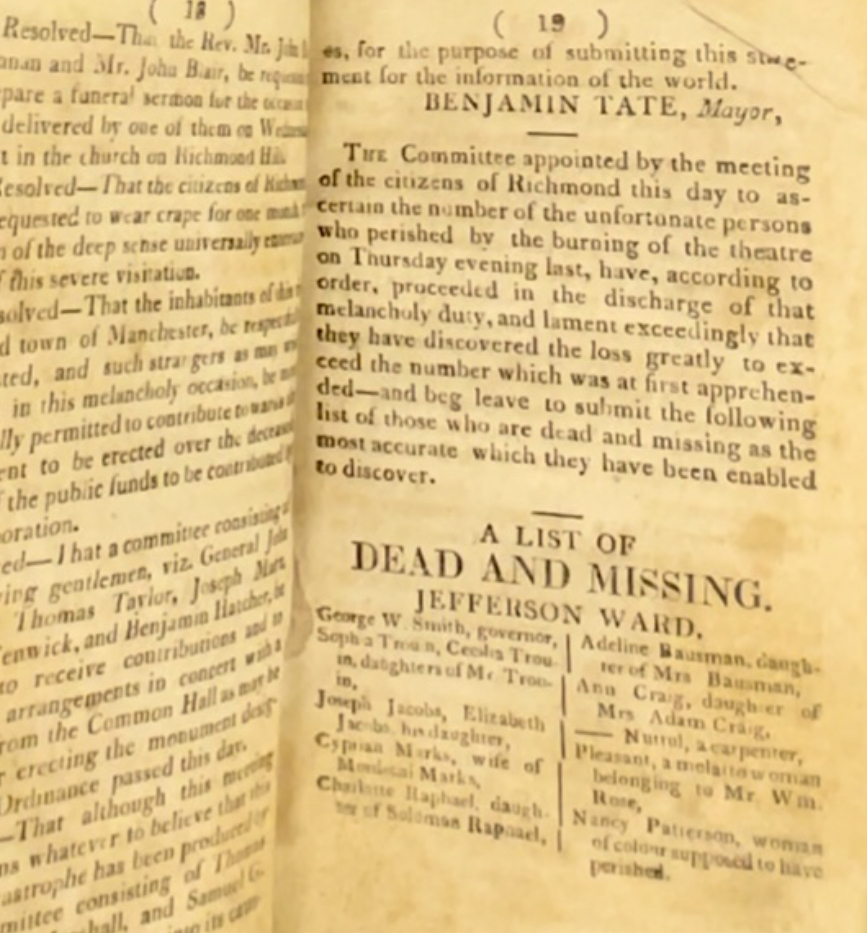

The Galvin Rare Books Room here at Boatwright has recently acquired a short book that is a collection of news articles, letters, and other miscellaneous documents related to the Richmond Theater fire. This book was published only two weeks after the fire had occurred in order to update the American public (particularly those living in Richmond) about the tragedy. The fire was the most deadly urban accident in the history of the United States at the time, with the death count totaling 72 individuals. Many notable figures within the political and economic atmosphere of the influential city of Richmond passed away or were greatly affected by the incident. The new governor of Virginia, George William Smith, who succeeded James Monroe, was tragically killed in the fire alongside “the President of the bank” and former U. S. Senator Abraham B. Venable. The book lists the names of those who died according to the Richmond neighborhood they lived in, and although many important male figures within the community passed, the majority of those lives lost were women.

The overall consensus (to current scholars and 19th century Richmonders alike) is that women were particularly susceptible to getting stuck in the building due to their heavy, frilled garments. The book recalls, however, many instances of those who attempted to save women and children who were caught in the fire. Two such gentlemen, Gilbert Hunt, a freedman who was not in attendance that evening, but witnessed the fire from a nearby shop, and Dr. James McCaw, a notable figure within Richmond’s medical community, aided women jumping from the second story by helping them jump onto a mattress on the ground floor. Hunt and McCaw saved over a dozen lives that night, and they are regarded after the fact as heroes of such a tragic event.

To commemorate the heroic work of those who saved lives and to honor those whose lives were lost, the Richmond community built a church upon the site of the theater, which was completed in 1814. This building, originally an Episcopal church, is still standing on East Broad Street as a historic landmark of the city. The church houses a crypt underground for those who passed in the fire. On the front steps of the church, there is a monument in the shape of a funerary urn. This monument is inscribed with the names of the 72 individuals who died. The white men who passed are listed on the front, facing Broad Street, and the white women and children are on the remaining three sides, while any enslaved persons are listed at the bottom of the urn.

The severity of the Richmond Theater fire was compared within the book to several other theater or fire related disasters throughout history. This comparison was made at the very end of the book, perhaps to remind the audience that these disasters, although horrific and tragic, were not isolated. This rare and unique book describing tragedy that came upon the city of Richmond that December night ends in such a way to remind the readers that Richmonders were by no means alone in their grief and that the lives of those who perished in the fire would be remembered.

For further reading on the Richmond Theater Fire, please consider The Richmond Theater Fire: Early America’s First Great Disaster by Meredith Henne Baker. Additionally, Historic Richmond’s website offers more information on Monumental Church. Rachel Beanland has recently produced a historical fiction retelling of the event and its consequences in The House Is on Fire.