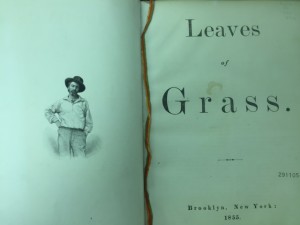

The Galvin Rare Book Room has a copy of the 1855 first edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. We were duly proud of this copy and used it in a display some months ago. A resident Whitman scholar, Rob Nelson, director of the Digital Scholarship Lab, saw it and was amazed that we owned one of the 158 known copies still extent. Sometime later, an antiquarian book seller’s catalog listed a copy for sale in excess of $170,000, making our book possibly the most monetarily valuable book in our collection and worth a little extra study.

The Galvin Rare Book Room has a copy of the 1855 first edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. We were duly proud of this copy and used it in a display some months ago. A resident Whitman scholar, Rob Nelson, director of the Digital Scholarship Lab, saw it and was amazed that we owned one of the 158 known copies still extent. Sometime later, an antiquarian book seller’s catalog listed a copy for sale in excess of $170,000, making our book possibly the most monetarily valuable book in our collection and worth a little extra study.

This edition has been widely studied, especially by Ed Folsom of the University of Iowa. In the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review in 2006, he printed a Census of the 1855 Leaves of Grass. He had collected information from all the known owners of the book looking for information about the various anomalies that make this edition so fascinating. He received answers from owners (including Boatwright) as to which binding they owned, the frontispiece picture, typos contained and changes made.

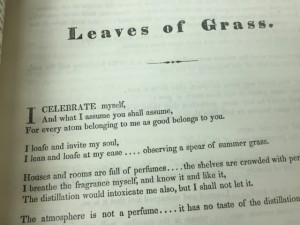

Leaves of Grass was a self-published work, and Whitman, himself a trained printer, set much of the type. It was printed at his friend Andrew Rome’s print shop in between runs of legal forms. Scholars believe this is the reason the book is so large—the paper on hand and the press were all set for legal forms. Also, Whitman proofread as the pages came off the press, so typos in one book of the same edition, do not appear in others. His miscalculations on how many pages his book would be, caused spacing to change and titles of poems to be dropped as printing  continued.

continued.

There are some famous anomalies to look for that are quite interesting. During the printing process, Whitman completely changed a line of “Song of Myself” from “The night is for you and me and all” to “The day and night are for you and me and all.” The earlier “night” version appears in 44 of the 158 copies, including Boatwright’s copy. While this difference was intentional, there are others that were not. The last line of “Song of Myself” either has a period or it doesn’t. (Boatwright’s copy does not.) Most scholars believe this is a press error, but some think Whitman was making a statement about open-endedness. Another glaring typo occurs in the final triplicate of the poem, “Failing to fetch me me at first keep encouraged.”

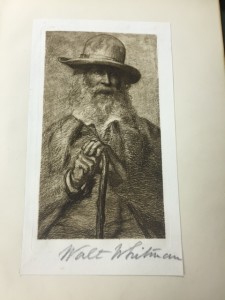

And then there is the most controversial of all, the frontispiece drawing. It is an engraving of a daguerreotype of Whitman, full body, wearing working clothes. There is an enhancement to the portrait that appears in all copies of the very first binding of the book (there are three different bindings of lesser and lesser value). The enhancement is known as the bulge, darker shading at the right of the crotch. Many of the second binding copies do not have this. Boatwright’s copy does, which helps place our copy in the earliest run of the book in June of 1855.

And then there is the most controversial of all, the frontispiece drawing. It is an engraving of a daguerreotype of Whitman, full body, wearing working clothes. There is an enhancement to the portrait that appears in all copies of the very first binding of the book (there are three different bindings of lesser and lesser value). The enhancement is known as the bulge, darker shading at the right of the crotch. Many of the second binding copies do not have this. Boatwright’s copy does, which helps place our copy in the earliest run of the book in June of 1855.

Whitman, the bookmaker, turns out to be almost as fascinating as Whitman, the poet. And, books as objects are equally fascinating.

+Folsom, Ed. “The Census of the 1855 Leaves of Grass: A Preliminary Report.” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 24.2 (2006): n. Web. 13 March 2014.