Note: This post was authored by Taylor McNeilly, Processing & Reference Archivist.

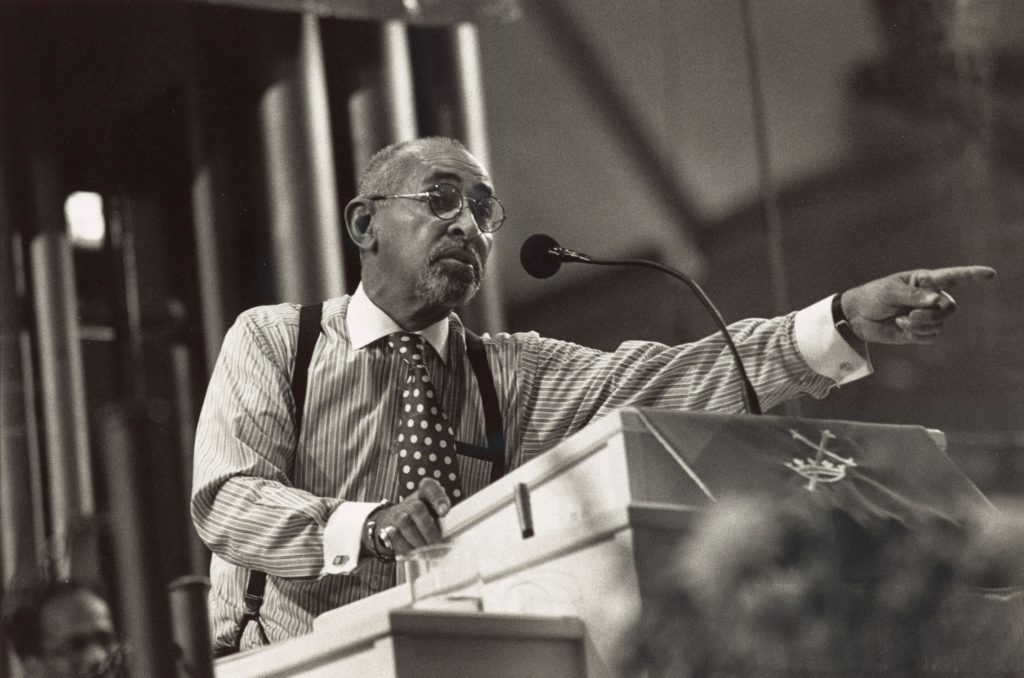

Welcome back to another #wyattwalkerwednesday! I know it has been a while since I posted any updates about the collection, but I have some big updates today to make up for it. In fact, I have what may be the most significant announcement to date: we are opening a portion of the physical collection for research! But first, some earlier updates about work we have done recently.

Just before and during the pandemic, we have opened up a number of digital portions of the collection. These started with what we call the Birmingham Tapes, recordings of ten mass meetings held during the Birmingham Campaign in 1963. Because these were thought to be the oldest audiovisual material in the collection, they were deemed top priority for digitization, since that process not only allows for easier access via the Internet but also preserves the material in a new, digital format. Magnetic media such as audio cassettes or VHS tapes have an estimated “shelf life” of approximately 40 years, so you can understand the concern we had for recordings that were nearly 60 years old.

After the Birmingham Tapes were digitized, preserved, and accessible online, we turned our attention to the nearly 700 recordings of Dr. Walker’s church services, most of which were held at Canaan Baptist Church of Christ in Harlem. While the digitization portion of this project is complete, the work to make them accessible is still ongoing – although we have made good strides in that since the last progress report I posted. We now have up to tape #275 available online along with the master inventory that lists the title and date of each recording (where that information is available). I will go into detail about this project in a future update, but progress continues.

Finally, we have also digitized and made available online the five film reels that were included with the collection. Although these are silent films, we worked with a prominent scholar in the field to transcribe these films, describing each scene for the visually impaired as well as providing a brief analysis of each. Dr. LeRhonda S. Manigault-Bryant, the scholar who provided the transcription and analysis, has our eternal gratitude for her illuminating work on this project that enabled us to make this material accessible online.

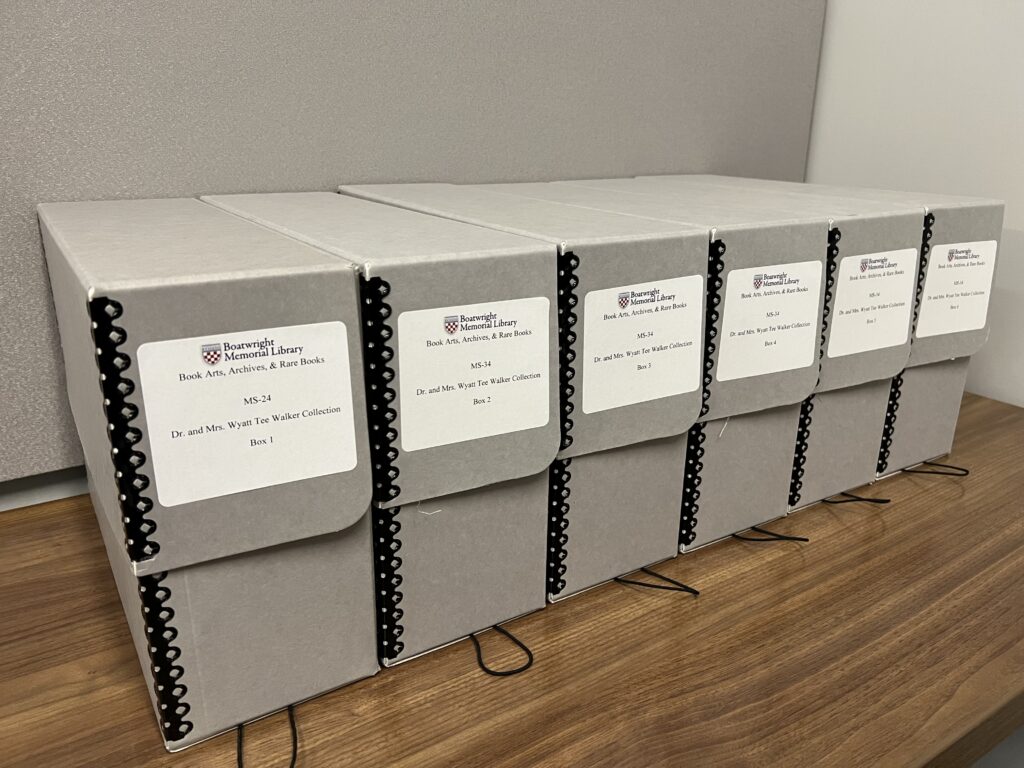

The nature of the pandemic and the University of Richmond’s response to it moved us into a purely digital work mode, but as we have returned to working in person, I have been able to return to processing the physical materials of the Dr. and Mrs. Wyatt Tee Walker Collection as well. After sorting through all of the physical material, I have focused my work on the earliest material first, and specifically on manuscript (unpublished, paper) material. I am happy to announce that I have now worked through all manuscript material dated up to Dr. Walker’s departure from SCLC in 1964!

Since Dr. and Mrs. Walker were already incredibly busy by 1964, this material is arranged into a number of series and subseries. Please note that these series and subseries may end up holding material from later (or much later) in Dr. and Mrs. Walkers’ lives, and that material is not yet available, meaning the series and subseries may not be fully open to research. You can view the finding aid, including a folder-level inventory of the material now open for research, in our online collection inventories.

If you have any questions or would like to request access to material, please email archives@richmond.edu and let us know what boxes or folders you would like to access. As we announced last week, we now have open hours four times a week and are happy to accommodate researchers who need to come in outside those hours by appointment.