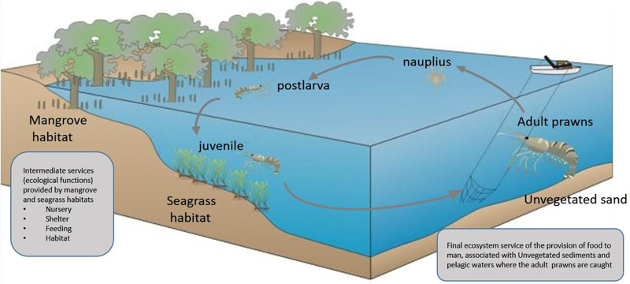

In collaboration with the Virginia Museum of Natural History, Boatwright Memorial Library’s Science Librarian, Heather Ervin, and Rare Books and Special Collections have put together a new exhibit case on the second floor of the library themed around visual science communication. Visual science communication is used in order to teach scientific ideas in a visual manner. This often means that scientists and artists must work together in order to create an educational piece of scientific visualization. Common representations of visual science communication are textbook depictions of nature, photographs, and videos.

Scientific visualization has changed greatly over the years. Even 30,000 years ago, human beings made cave paintings of animals that they came into contact with. Although art historians and scientists alike are unsure what the intent was behind these scientific artworks from the Paleolithic period, we are able to conclude that by rendering human forms, plant life, and animals in a scientific manner with pinpoint accuracy became important to the teaching and learning of not only art, but science as well. These two areas of study revolved around each other, and it would be difficult in many regards to separate the two.

With the invention of the printing press, scientists were able to share and spread knowledge of animals and plants much more easily, and with the ability to print drawings of the animals and plants discussed in the texts, anyone who possessed the book could now have an image of the specimen in their minds. This trend of visual science communication continues to this day.

The exhibit in collaboration with the VMNH honors this culture of visualizing science by incorporating preserved specimens from their collection, including a snapping turtle, box turtle, viper, cowfish, fence lizard, spotted salamander, rattlesnake rattles, and seahorses. In addition to the physical specimens provided by the museum, the Rare Books Room has provided several books with drawings of similar specimens in text.

As our world becomes increasingly digital, it is still important to preserve physical objects that communicate visual science. The digital world does, however, continue this tradition of visual science communication in an accessible manner, which not only helps those who are trying to learn about a particular science, but also preserves the trend of visualizing science for generations to come.

We appreciate the opportunity to work with the Virginia Museum of Natural History, with special thanks to Marshall and Arianna.

Books displayed:

The animal kingdom, arranged according to its organization… by P. A. Latreille and Georges Cuvier. QL45 .C944 v.2

Brehm’s illustriertes Thierleben fur Volk und Schule; bearbeitet von Fredrick Schodler by Alfred Edmund Brehm and Friedrich Schoedler. QL 605.4 .S22 1897 v.3

Animate creation; popular edition of “Our living world”… by J. G. Wood and Joseph B. Holder. QL 50 .W882 1885

Popular zoology by Joel Dorman Steele and J. W. P. Jenks. QL 48 .S8 1887

The Riverside natural history… by J. S. Kingsley and Friedrich von Hellwald. QL 45 .K56 1888 v.3

For further reading, check out the libguide made by Heather Ervin at https://libguides.richmond.edu/bio_display_SP24, and consider reading Visual Science Communication: Learn About It. (n.d.). Guild of Natural Science Illustrators at https://www.gnsi.org/visual-scicomm.

I agree completely. While digital platforms are invaluable for making scientific knowledge accessible, there’s something irreplaceable about preserving physical objects that visually communicate scientific concepts. It’s essential to blend traditional methods with digital advancements to ensure that future generations can continue to appreciate and learn from visualized science.