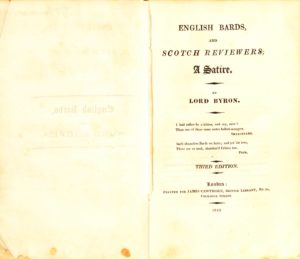

(Note: This post was authored by Jon Tuttle, Special Formats Cataloger) Boatwright’s 1810, third edition of Lord Byron’s English Bards and Scotch Reviewers is, as its catalog record suggested it might be, a spurious edition. It was most likely produced not in 1810 but two years later and without Byron’s knowledge by his old publisher, James Cawthorn. Reading about our spurious English Bards led me, disorientingly, to three literary forgers: Cawthorn, Thomas James Wise, and George Gordon De Luna Byron, introduced here in a series of three posts that tell the story of a forgery, later verified as such by a forger, who was himself the victim of a forgery.

George Gordon De Luna Byron, a.k.a. de Gibler

While English Bards was flying out of London bookshops, its author toured Cádiz. There, according to one source, Byron met and married a Spanish countess. Returning to England two years later, Byron ignored the marriage, which at that time would have been void anyway. His secret bride, the Countess De Luna, wrote to him from her death bed some thirteen years later, informing him of the existence of their illegitimate son. In Greece and on his own death bed, Byron died before receiving the letter.

This story, which is probably untrue, comes from the man who claimed to be that son of Byron and the Spanish countess, a man who called himself, at times, Major George Gordon De Luna Byron, and, at others, de Gibler. What we know about his adult life, that he was a literary forger, and the fact that no one has corroborated his stories, makes what he wrote about his youth more than a little suspect. He may or may not have studied in Switzerland; he may or may not have lived in Virginia.

We do know he left the States for London in 1844, where he continued a letter-writing campaign to Byron’s publisher and family members. In these elegant, polished letters he laid out his relation to Byron, described his hardships, and asked for money. The year before, he even asked for an example of Byron’s autograph. “No doubt he was even then, in 1843, practising that art of imitation of Lord Byron’s handwriting which later he managed to bring to such a high degree of perfection,” wrote his biographer. For while in London de Gibler began in earnest an entirely different kind of letter-writing campaign, one in which he copied the correspondence of poets like Byron and Shelley, sometimes altering the letters with new texts, perhaps making up some himself, then slipping the letters onto the market.

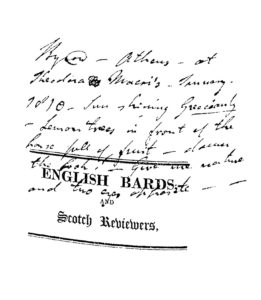

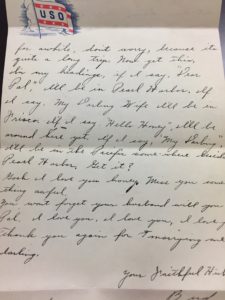

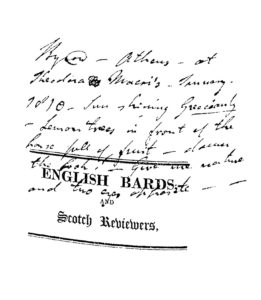

Wise, the ubiquitous bibliographer of Byron, whose own stories of an upper class childhood were “probably unprovable” or “probably untrue,” tried to alert the buying public to his predecessor in forgery. In his bibliography of Byron, Wise describes a copy of the authorized second edition of English Bards, which includes an inscription purportedly from Bryon himself: “sun shining Grecianly—Lemon trees in front of the house full of fruit—damn the book!—Give me nature and two eyes opposite.” But the inscription, Wise concludes, “is not genuine. It was the work of the man de Gibler.”

Wise, the ubiquitous bibliographer of Byron, whose own stories of an upper class childhood were “probably unprovable” or “probably untrue,” tried to alert the buying public to his predecessor in forgery. In his bibliography of Byron, Wise describes a copy of the authorized second edition of English Bards, which includes an inscription purportedly from Bryon himself: “sun shining Grecianly—Lemon trees in front of the house full of fruit—damn the book!—Give me nature and two eyes opposite.” But the inscription, Wise concludes, “is not genuine. It was the work of the man de Gibler.”

Wise was not always so quick to ring the alarm, however. He relied in part on an 1872 book called the The Unpublished Letters of Lord Byron to flesh out Byron’s scandalous lifestyle for the two-volume bibliography. Seventeen of the letters are addressed to a lover, “L.,” one of which alludes to a child born out of wedlock: “the child ***** is dead, and I do not regret it, though a bastard Byron is better than no Byron.” Wise could not help but include the story.

Unfortunately The Unpublished Letters of Lord Byron was a dubious volume. Some of the letters were in fact already published, and some of them, like the letter about yet another never-before-mentioned child, were likely created by de Gibler in his campaign to gain proximity to the life and fortune of Byron. Disappointed to discover the book was not what it pretended to be, the publisher pulped all but ten copies of it before sale. One of those copies came to be owned by Harry Buxton Forman, and from Forman it changed hands to his partner, Wise. Byron experts pleaded with him to reconsider mentioning the “L.” letters in his work, but Wise insisted the letters were utterly Byronic; he salted his bibliography with them anyway.

These then were spurious texts cited in a bibliography, which is now cited in the catalog records of spurious books. From the time I began cataloging our copy of English Bards it seemed there was a compromised book under every rock turned. Like all catalogers I stuck to a principal of representation when working with English Bards, representing the book as it represented itself, that is, transcribing things like year and edition from the title page. But in the case of English Bards, representation isn’t enough when telling our students and faculty exactly what we have. A second, more challenging principal, accuracy, instructs catalogers to give extra information correcting any ambiguous or misleading statements. To correct my description of English Bards I reached for reference sources. All confirmed that our edition was spurious, but they also surrounded it with a parade of nineteenth century fraud. With each step in my reading trust gave way and the lesson was repeated: a book is not always what it says it is, a title page can lie to you.

References

Ehrsam, Theodore G. Major Byron: The Incredible Career of a Literary Forger. Charles S. Boesen, 1951.

Barker, Nicolas and John Collins. A Sequel to An Enquiry into the Nature of Certain Nineteenth Century Pamphlets by John Carter and Graham Pollard: the Forgeries of H. Buxton Forman and T.J. Wise Re-examined. Scolar Press, 1983.

Wise, Thomas James. A Bibliography of the Writings in Verse and Prose of George Gordon Noel, Baron Byron. Dawsons of Pall Mall, 1972.

Partington, Wilfred. Thomas J. Wise in the Original Cloth: the Life and Record of the Forger of the Nineteenth-century Pamphlets. Dawsons of Pall Mall, 1974.

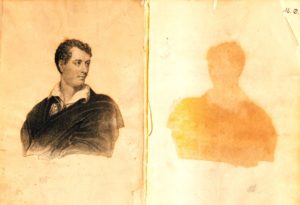

Lord Byron on his Death-bed from Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of inscription from Wise, Thomas James. A Bibliography of the Writings in Verse and Prose of George Gordon Noel, Baron Byron. Dawsons of Pall Mall, 1972.