(Note: This post was authored by Taylor McNeilly, Processing & Reference Archivist.) Welcome back to another #WyattWalkerWednesday post! This week, we’re keeping up our every other week updates on the A/V materials pattern.

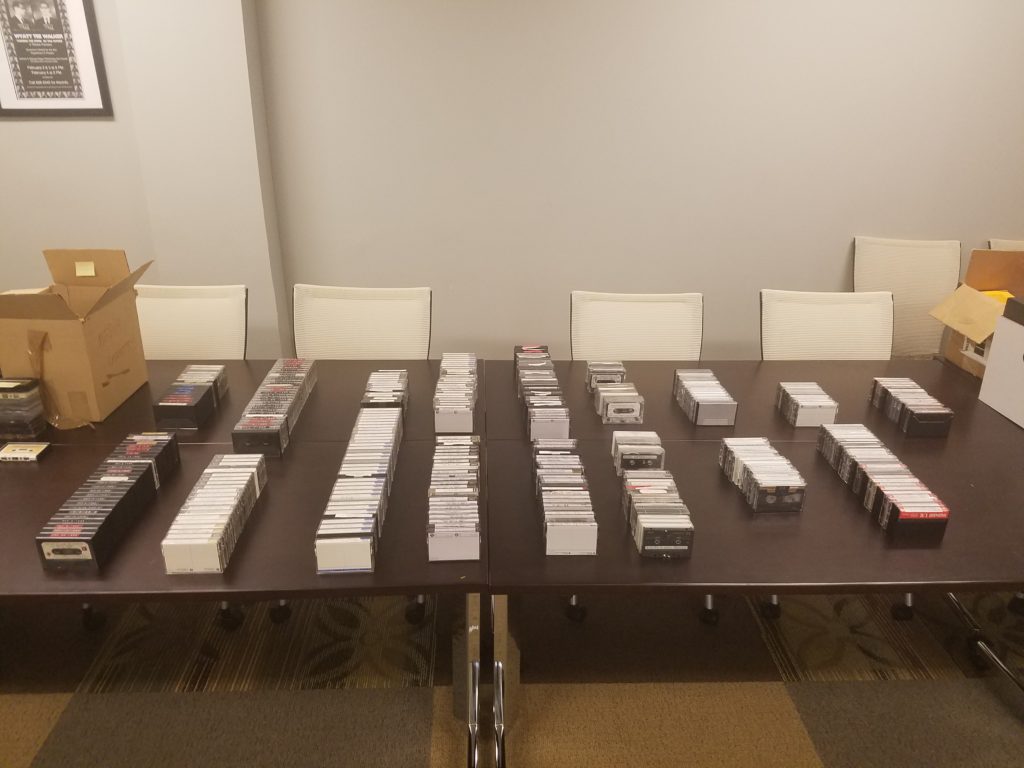

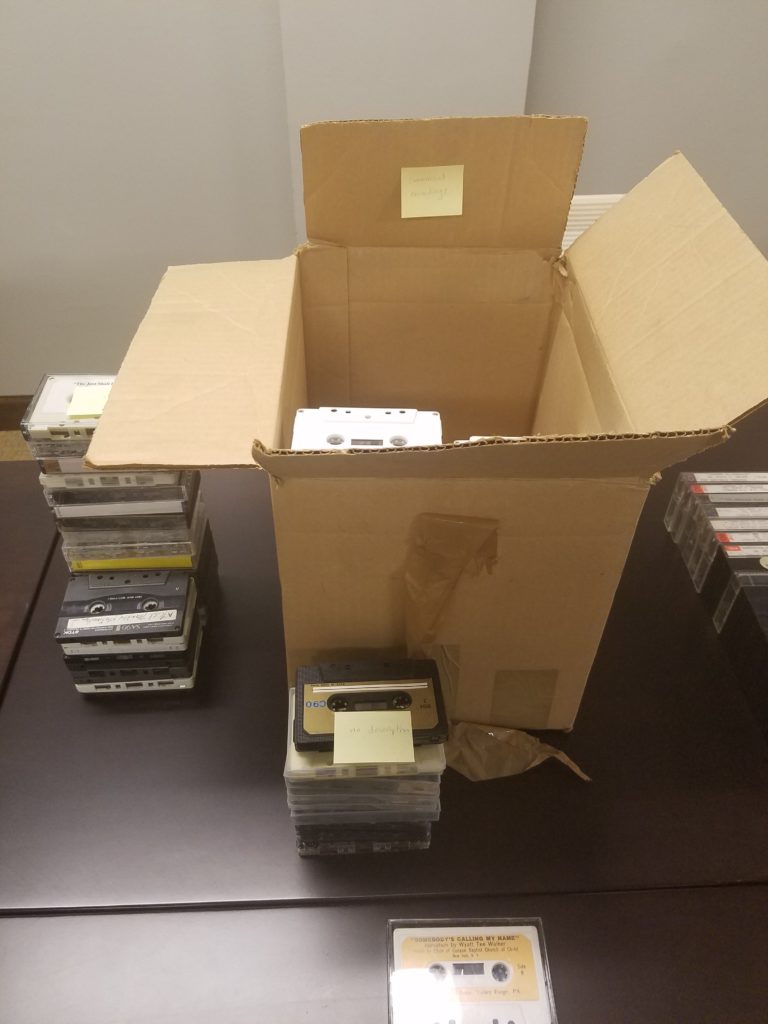

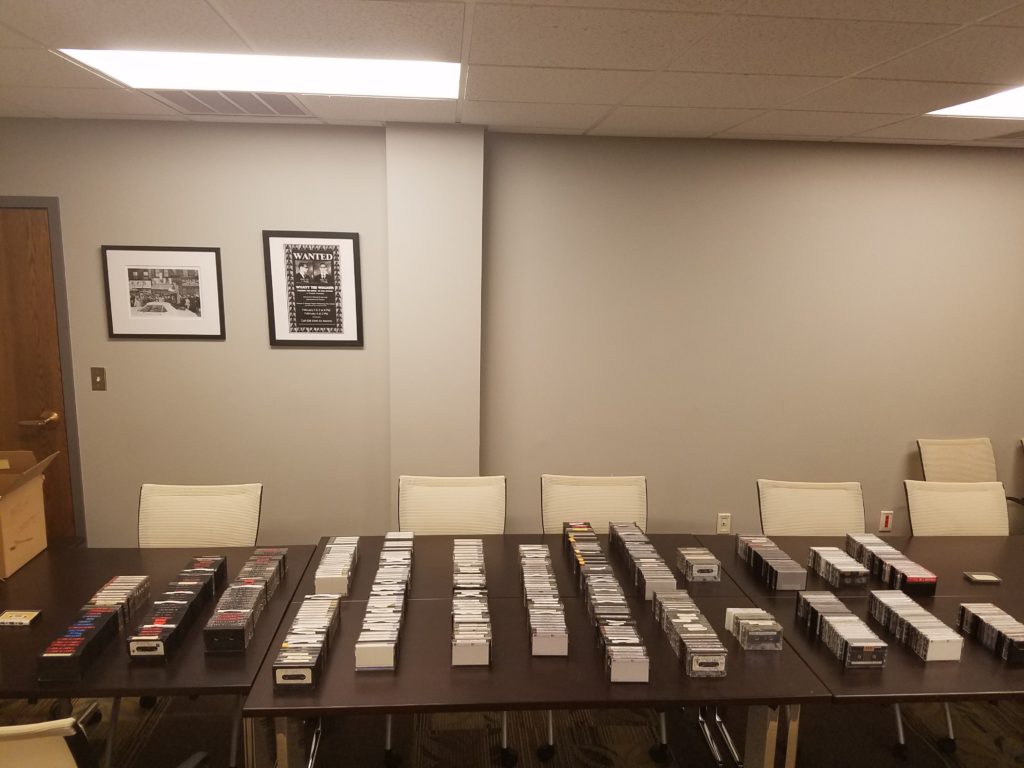

Approximately 500-600 audio cassettes, arranged chronologically. The box on the left edge of the image is commercially produced cassettes, separated from the main work of the collection.

When last I gave an update on the audio cassettes, I was busily arranging them into chronological order, with commercially produced cassettes separated out. This work is almost done – 800 cassettes is a lot to sort through, and unfortunately I do have other daily duties – but progress has also been being made on the inventory.

You may recall I mentioned the inventory last time. It was compiled by some student workers before my time on the project, and it lists each cassette by name and date, as well as speaker whenever possible. Unfortunately, the cassettes weren’t listed in any consistent order, and the dates were written in a way that didn’t allow for sorting the inventory chronologically. Since I’m arranging the cassettes chronologically, I was faced with a dilemma: either clean up the date column, normalizing the data into a format that Excel can sort, or number the cassettes in the inventory one at a time after physical arrangement was finished.

Both of these options have pros and cons. If I wanted to normalize the data, it would be time-consuming to retype 800 date fields, but it would mean I could sort the inventory and save time during the packing process. If I left the dates as is, I could finish arranging the physical cassettes faster – but I’d have to do the date normalization at some point in order to send it out to the digitization vendor.

There were a handful of other factors that tied into the decision, but in the end I decided to take a quick break from arranging the physical cassettes to update the inventory. This started with normalizing the date column, allowing me to sort the inventory into the same order that they should be physically. This also proved useful at cleaning up the data, as there were occasional typos (a year listed as 19846, for instance). I also created a new column to indicate commercially produced cassettes, allowing them to be sorted separately from Dr. Walker’s sermons and church recordings. Since these are physically separated, this is another major improvement that should make things much easier as we prepare a spreadsheet for the digitization vendor.

The physical arrangement is also coming along well, with approximately 600 of the cassettes separated into commercial and non-commercial recordings and arranged chronologically. With about 200 cassettes left to arrange, I’m hoping to be finished with the arrangement before the Memorial Day weekend, and listing and packing can begin next week.

As always, I’ll continue posting updates here, and with luck you’ll see another discussion of the A/V materials in two weeks. Keep in mind that the audio cassettes aren’t the only material being digitized – the 8mm films, 16mm films, and audio reel are also being included in this project! There’s plenty more to do, so keep an eye out for further updates.