(Note: This post was authored by Taylor McNeilly, Processing & Reference Archivist.) Previous #wyattwalkerwednesday posts have discussed the close friendship and collaboration on civil rights work between Dr. Walker and Dr. King. Today, which marks the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, seems a poignant moment to look at both men, their friendship, and their legacy.

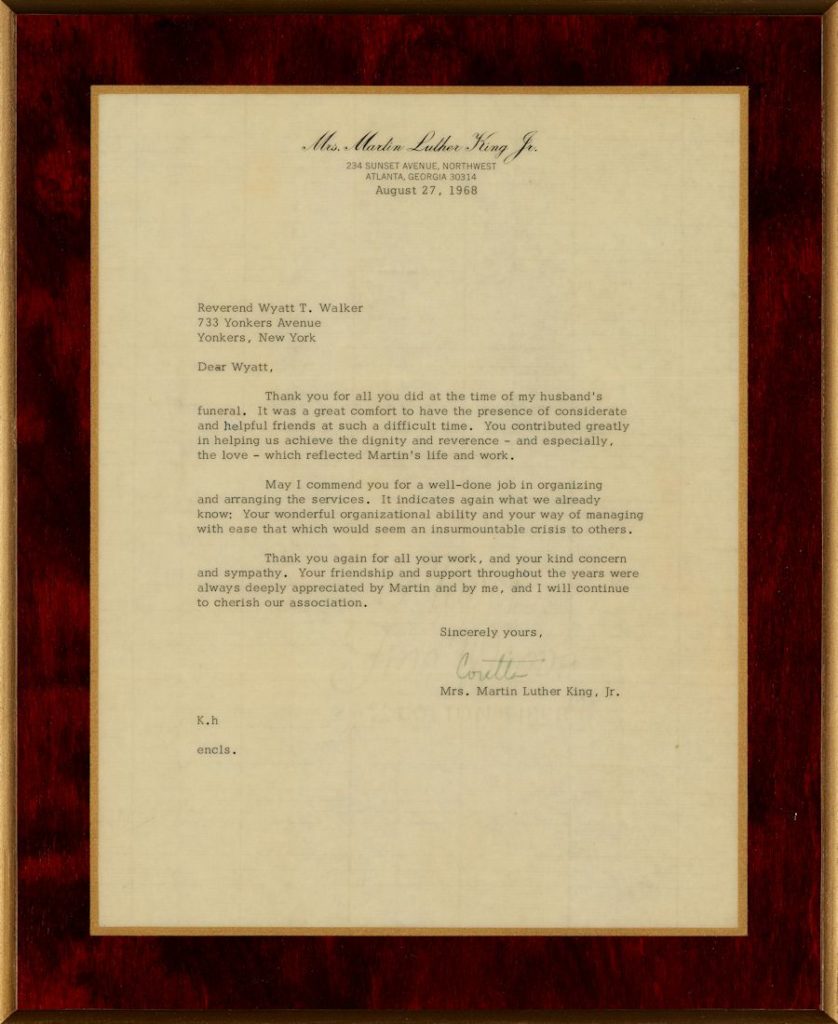

A letter, framed, from Coretta Scott King to Dr. Walker, thanking him for his work in organizing Dr. King’s funeral and support after Dr. King’s assassination.

Dr. Walker and Dr. King first met in the early 1950s while they were both at seminary, presidents of their respective classes and in charge of their respective inter-seminary groups. Dr. Walker credits Dr. King’s work as the reason he first accepted the non-violent approach to civil rights work, and we have correspondence in the Dr. and Mrs. Wyatt Tee Walker Collection between Dr. Walker and Dr. King discussing this approach to protest from as early as the late 1950s, when Dr. Walker was pastor at Gillfield Baptist Church in Petersburg, VA. In fact, we have a letter from Dr. King to Dr. Walker from late 1958 expressing Dr. King’s support for Dr. Walker’s “Prayer Pilgrimage,” a protest Dr. Walker had discussed with Dr. King during a visit to the King family. The Prayer Pilgrimage was a march held on New Year’s Day of 1959, starting at a mosque in Richmond, leading across a dozen or so blocks, and ended at the south portico of the Virginia State Capitol. This march, titled in full a Pilgrimage of Prayer for Public Schools, was held to protest Virginia’s resistance to the integration of public schools. Dr. King recorded remarks and sent them to be played at the march as a show of support, for which Dr. Walker thanked him profusely in a later letter.

Of course, Dr. Walker and Dr. King began working together much more closely in 1960, when Dr. Walker was made the first full-time director of SCLC and the unofficial right hand man of Dr. King. The next four years would prove wildly successful for both men and SCLC, culminating in such notable milestones as A Letter From Birmingham Jail, the March on Washington and “I Have A Dream” speech, and the 1964 Civil Rights Act. While Dr. Walker left SCLC in 1964, he and Dr. King remained close friends. Ten days before his assassination, Dr. King installed Dr. Walker at his installation service at Canaan Baptist Church of Christ in Harlem. In his oral history interview for the University of Richmond, Dr. Walker notes that this installation service was the last time Dr. King preached in New York before he was killed.

But the story of Dr. Walker and Dr. King does not end with Dr. King’s death. Coretta, recently widowed, reached out to ask Dr. Walker for his assistance in planning the funeral and homegoing service, including the march to Morehouse. This final service to Dr. King, attended by some 400,000 people, was one of Dr. Walker’s “capstones” as an organizer.

And so today is a day for remembrance, not only of the man Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was, but of the work he and Dr. Walker did for this country in the 1950s and 1960s. Their fight against the racism woven into the fabric of American culture and government, the economic inequality of American life, and the progress they made against these forces not only improved the lives of Americans, but have become a memorial of their work together and lifelong friendship. Much as Dr. Walker felt that he was part of “the unfinished revolution of 1776,” his work and Dr. King’s did not end with their passing, a message that should be held close in all our hearts on this anniversary.

In honor of Dr. King, the University of Richmond will be taking part in an international tolling of the bells. The University’s bells will toll 39 times at 7:05pm, marking Dr. King’s 39 years on Earth at the minute his death was announced nationwide.