(Note: This post was authored by Taylor McNeilly, Processing & Reference Archivist.) Processing a collection is always a fun exercise in observation: you always have to make sure you’re keeping a sharp eye out for information that might help researchers in the future. But sometimes the things you spot as a processing archivist can be less than helpful! For today’s #WyattWalkerWednesday, I talk about one such discovery I recently made in the Dr. and Mrs. Wyatt Tee Walker Collection.

Often, processing a collection is a bit like working as a psychologist or therapist: you have to get inside the mind of the collection’s creator to figure out how they organized their material, why they organized it that way, and why they kept these specific things in the first place. For much of Dr. Walker’s material, much of this is self-evident, especially in the case of the SCLC files. Most materials are in clearly labeled folders that often shed light on their contents, but occasionally I stumble across something with a little more mystery surrounding it.

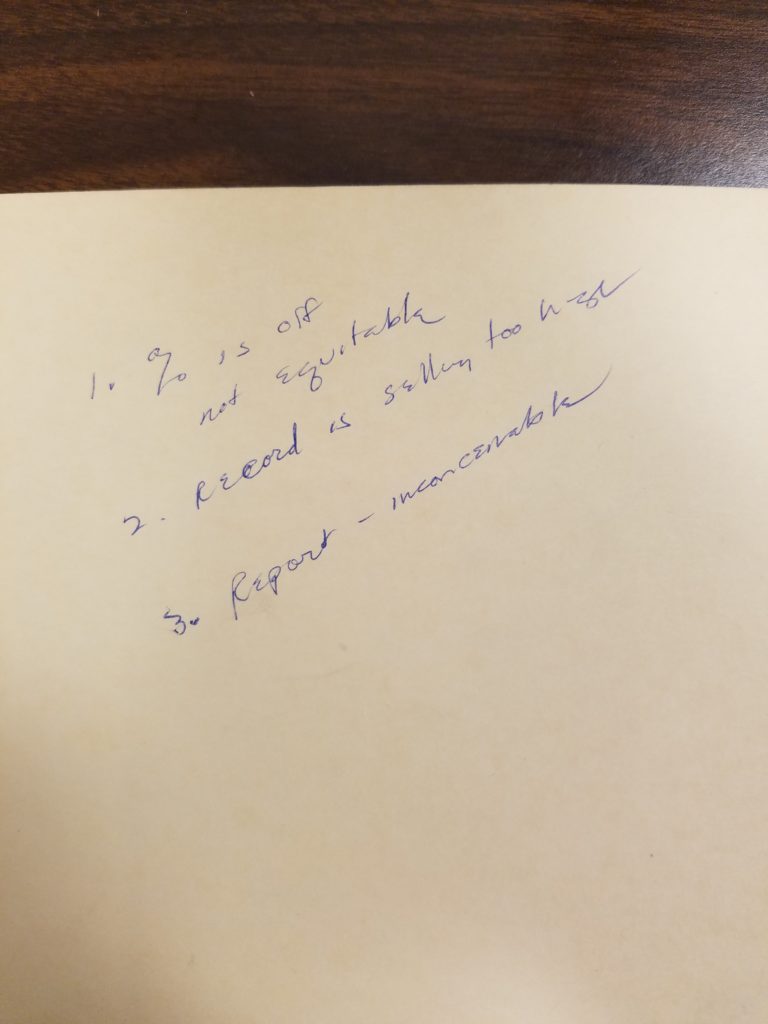

Take, for instance, an empty folder I found among the other files. There were no materials in the folder, and the spot most often labeled was blank. Perhaps the folder was accidentally filed and never removed, or perhaps its contents were tossed at some point. Not a big deal, no reason to keep it. Until I went to flip the folder closed, when I discovered writing inside the flap.

I’ll admit that this text, written in what appears to be Dr. Walker’s hand, is almost meaningless without context. SCLC published several audio records, primarily on vinyl and mostly of Dr. King’s various sermons and speeches during SCLC events. It’s likely that Dr. Walker took these notes about one such record, but without knowing which record – and when this was written – this has almost no bearing on potential research. Which record, published by whom? Is the % mentioned the percentage of profits paid to SCLC by the publisher? What report is so inconceivable and why?

What I found most amusing, to be honest, was this use of the word “inconceivable.” While these notes were almost certainly written during Dr. Walker’s time at SCLC in the early 1960s, a full decade before The Princess Bride was published and almost 15 years before the popular film adaptation, my first thought was of Wallace Shawn proclaiming that line. In this case, however, I believe the word means exactly what Dr. Walker thought it means. And in his use of the word, as is the case in so much of his life, Dr. Walker was far ahead of the curve.

As always, please check back next Wednesday for another peek into the Dr. and Mrs. Wyatt Tee Walker Collection, my processing progress, and some of the materials I find in my work!