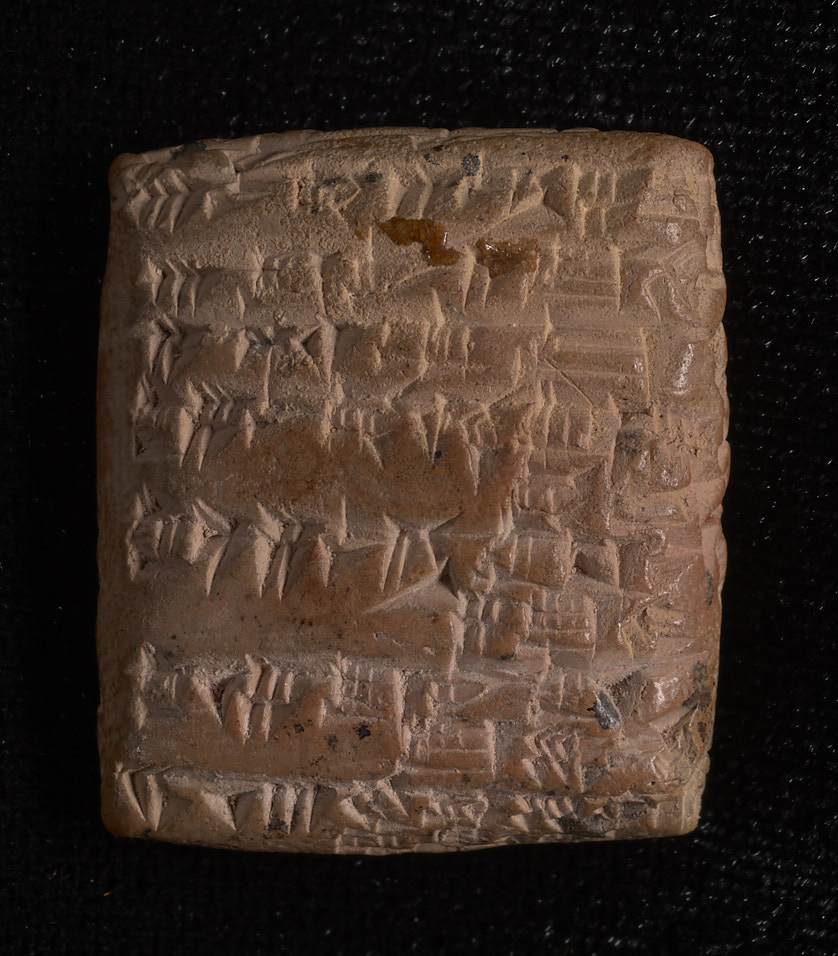

Did you know that we have a cuneiform messenger tablet in our Rare Book collection? Do you know what a “cuneiform messenger tablet” is? Back in 2350 BCE, a scribe at a temple in Umma, Sumer (present-day Iraq) repeatedly pressed his wedge-shaped stylus into a 3cm x 3cm clay tablet, recording a “list of provisions supplied to the temple, including oil, meat, dates, and grain. On the edge in fine characters is the date.” Picture a frosted mini-wheat, minus the frosting, and that’s kind of what our tablet looks like. It’s basically a 4,000-year old inventory or accounting document, small enough to be easily transported by a messenger who would then deliver it to be read by another scribe.

Can I read cuneiform? No, no I cannot. Can you read it? Well, you can make a research appointment to study it, but you can’t touch it. So how can you study it? Spring semester of 2024 gave us the opportunity to figure that out.

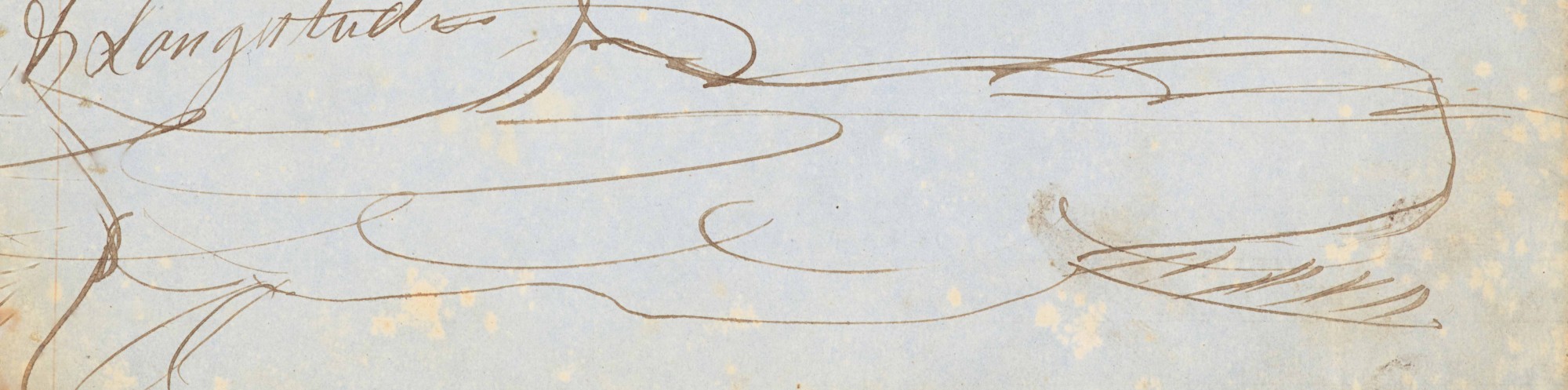

Professor Elizabeth Baughan, Department of Classical Studies, accompanied one of her students on his research visit to study the tablet. They wore gloves while examining the tablet, but their cell phone photos couldn’t quite capture the detail they needed to further study the tablet on their own time. We enlisted the help of our colleague, Warner, in the Digital Scholarship Lab and the DSL’s high-resolution camera. Those photos turned out much better. One of them will even be used for the thumbnail in the tablet’s catalog entry. But high-res photos still don’t solve the problem of getting your hands on history.

We reached out to Nathan Hilliard-Hansen, the Studio Art Lab Manager, to see if he had the tools to scan the tablet and render a 3D model. He did! Natalie & I met up with Prof. Baughan at Nathan’s lab. Even though his equipment has been able to scan many different objects, including coins, with high-fidelity, the texture of our tablet proved too much of a challenge for the scanning software.

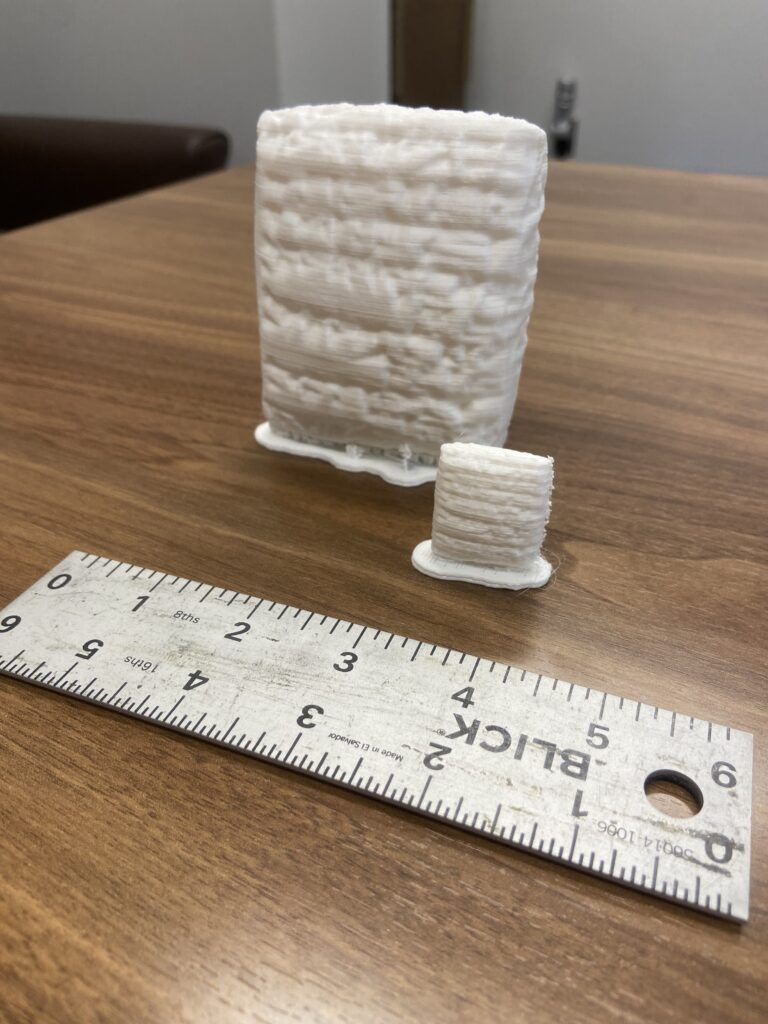

Undaunted, Prof. Baughan reached out to her colleague at VCU, Bernard Means of the Virtual Curation Lab. Natalie escorted the tablet to Prof. Baughan’s lab where Bernard had his equipment set up. A few weeks later, he produced digital files and two 3D-printed models! One life-sized, and one jumbo-sized. The 3D prints don’t quite capture the full detail of the cuneiform, but it’s a tablet you can hold without giving us in the Rare Book Room a heart attack!