The Reverend Dr. Wyatt Tee Walker with his wife, Theresa Ann Walker, 2017.

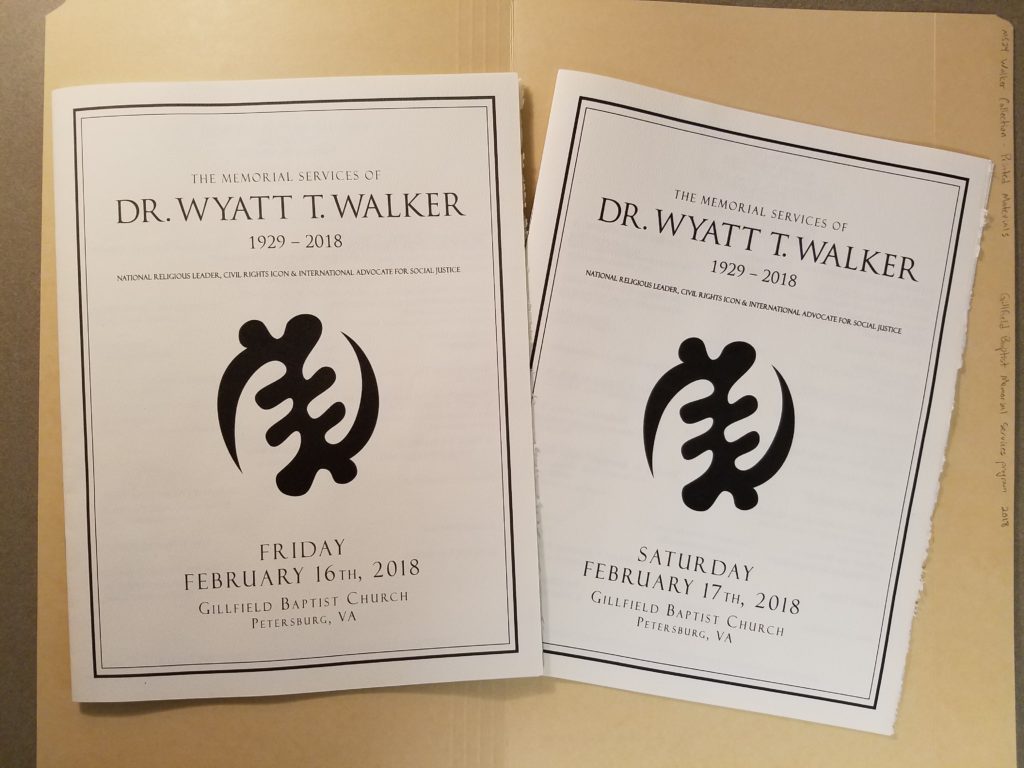

(Note: This post was authored by Taylor McNeilly, Processing & Reference Archivist.) Today we mourn the passing of the Reverend Dr. Wyatt Tee Walker. Dr. Walker passed away Tuesday morning after a long and active life, surrounded by his family.

Various biographies of Dr. Walker are widely available, including the short, introductory biography I wrote in my first blog post. In the past day, major newspapers and other sources have published works honoring and remembering Dr. Walker, including the University of Richmond. However, it seems an appropriate time to discuss more of Dr. Walker’s life in detail particularly through the lens of the primary source material he and his wife, Theresa Ann Walker, generously donated to the University of Richmond in 2015.

While doing preliminary processing of Dr. Walker’s material, I have looked through much of the material he donated, discovering many different facets of Dr. Walker along the way. (This is one of the many reasons I’m so eager to process the collection and open it to researchers: the nuanced life and personality of Dr. Walker is amazing to discover, and I sincerely look forward to the research opportunities this collection will open up.)

My initial blog introduction to Dr. Walker did not mention the fact that he was a strong, outspoken activist for the anti-apartheid movement and served as an election monitor during the free election in South Africa. In fact, he was so well recognized within the movement that Nelson Mandela visited Dr. Walker and Canaan Baptist Church during his first visit as President of South Africa to the United States in 1994.

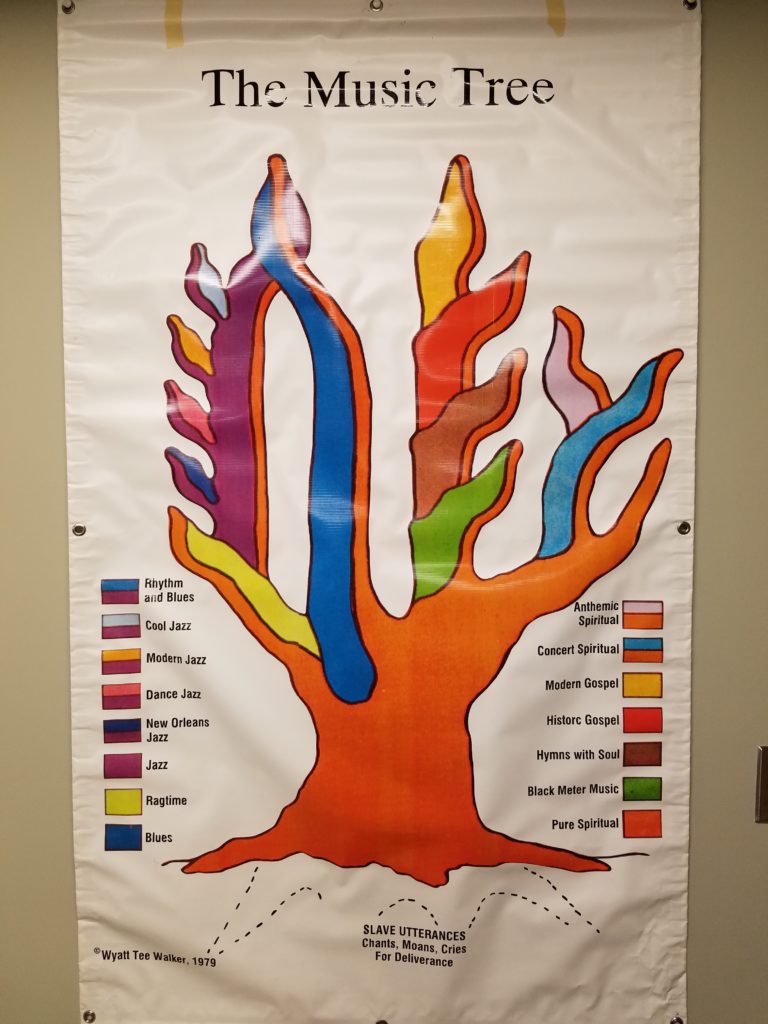

Dr. Walker’s music legacy is also far larger than previously mentioned. Beyond being a preeminent scholar and expert on black gospel music, Dr. Walker composed his own music in that musical tradition. He also revived the musical fervor at Canaan Baptist Church, eventually leading the church to produce multiple choral albums. Canaan Baptist continues to have a choral group named for their pastor emeritus, the Wyatt Tee Walker Inspirational Chorus.

Dr. Walker is recognized as a leading expert on the black gospel tradition not only in America, but also abroad. One of his many international trips brought him to Japan, where he interacted with the Kobe Mass Choir under the direction of Hisashi Kajiwara. Kajiwara later worked with the Kobe Mass Choir and the United Church of Christ in Japan to translate and publish Dr. Walker’s book Spirits that Dwell in Deep Woods in Japan. Kobe Mass Choir recorded an album of hymns Dr. Walker had selected or written that was published as a supplement to the book. (These materials are listed in the Boatwright catalog here.)

On a related note, Dr. Walker’s friends weren’t limited to world famous civil rights leaders and national leaders. One of the books donated alongside Dr. Walker’s papers is an autographed copy of Jackie Robinson’s Baseball Has Done It. In the inscription to Dr. Walker, Robinson states “it’s an honor to list you among my closest friends.” The catalog record for this volume, with the full inscription, is available here.

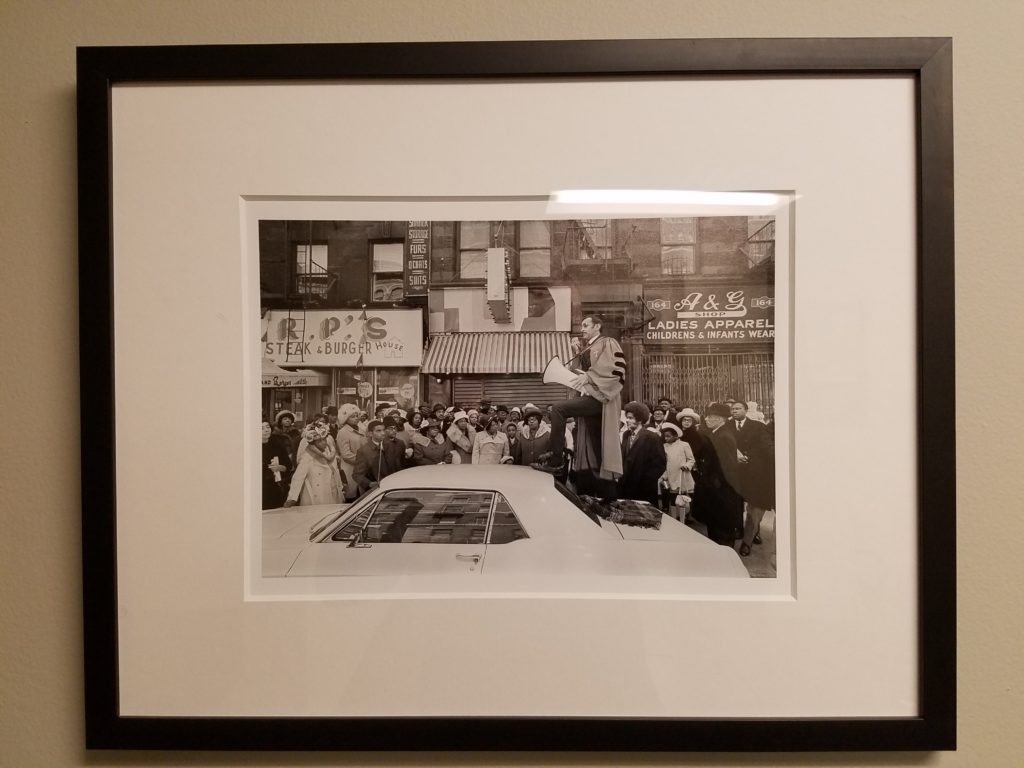

As previously mentioned, Dr. Walker’s work in Harlem went beyond his work as pastor of Canaan Baptist Church. For ten years, 1970-1980, Dr. Walker served as Special Assistant for Urban Affairs to Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Dr. Walker was also the largest single developer of affordable housing in New York City, and the co-founder of the first charter school approved by the State University of New York, the Sisulu-Walker Charter School of Harlem.

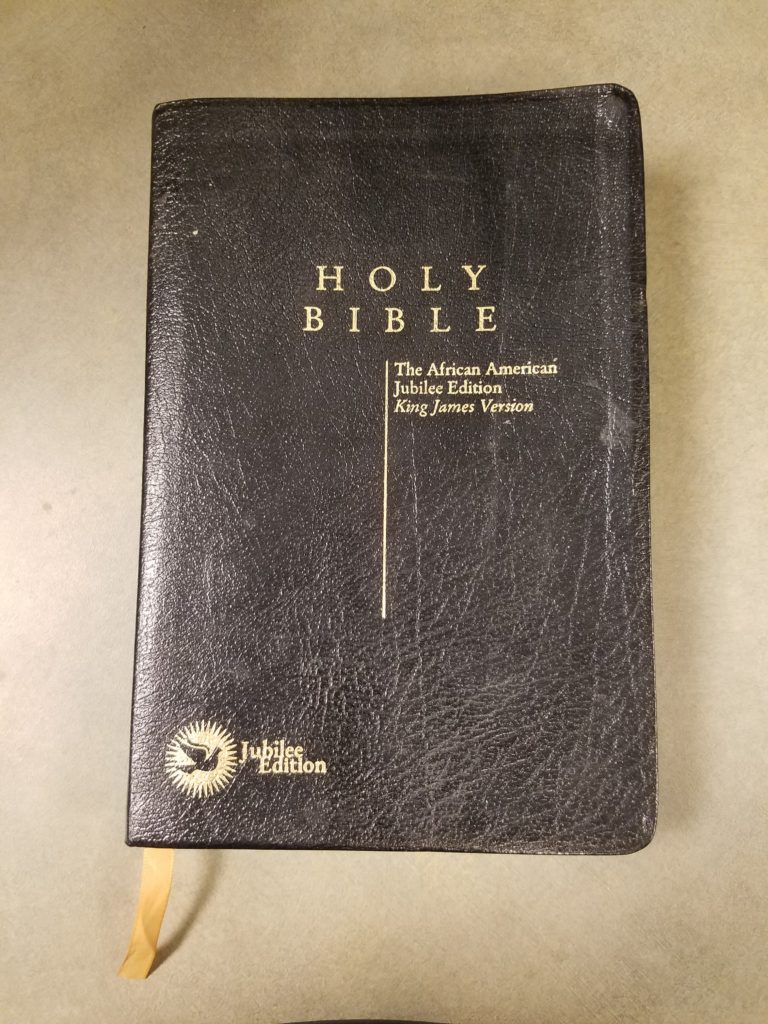

In between all of these laudable achievements, Dr. Walker somehow found time to write and publish countless works. He has published over 30 books and countless essays in between weekly sermons. Many of his published books can be found in our catalog. Canaan Baptist Church also recorded many of his sermons, beginning in the early 1980s. These were donated as part of the collection and are currently undergoing preservation work before being opened to the public.

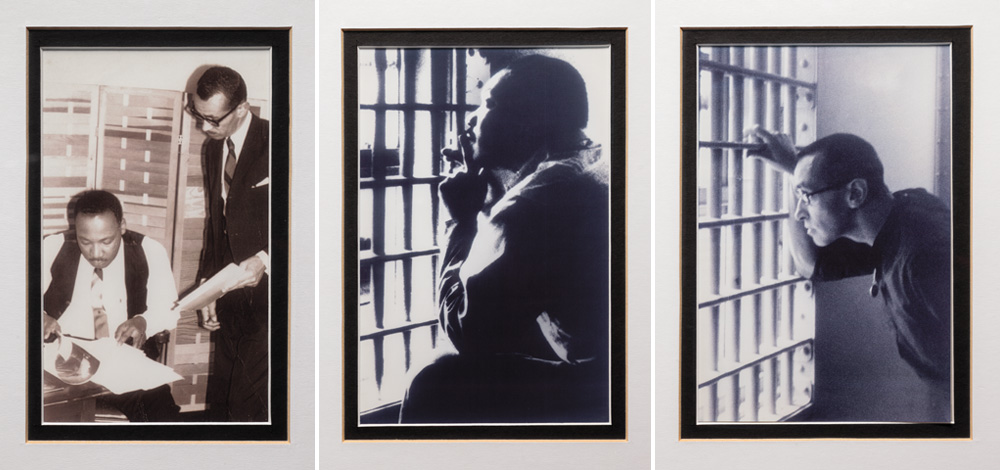

Alongside the numerous audio recordings of his sermons, Dr. Walker also donated a huge collection of personal slides. While some of these slides are images taken during Dr. Walker’s activism or work, including images of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Coretta Scott King, Rev. Jesse Jackson, and Rev. Ralph Abernathy, the majority of these slides portray Dr. Walker’s personal life and travel.

In his spare time (between being Dr. King’s right hand man, the largest single developer of affordable housing in NYC, leading anti-apartheid efforts, and all of his work in churches both musically and pastorally), Dr. Walker seems to have greatly enjoyed traveling. While we have not processed all of these slides, locations pictured in the slides we have looked at include Israel, London, Spain, Jamaica, Tangiers, the Soviet Union, Haiti, Mexico, Aruba, Portugal, Egypt, China, and Cuba. There are also many slides of family gatherings and events, including a World’s Fair and baseball games. These slides date from as early as 1960 continue into the 1980s at least, showing a personal side of Dr. Walker that may never have been seen before. The two-part oral history Dr. and Mrs. Walker graciously agreed to as part of the collection is another unadulterated glimpse into the personality of this astounding man.

The Reverend Dr. Wyatt Tee Walker lived a life full of love, determination, and a strong sense of justice. While his life’s work may defy a simple description, everything he did seemed focused around these concepts. Now, as that life has drawn to a close, we wish to honor his memory not just for everything he has done but for who he was. While his many and varied accomplishments are well known, the person who was Dr. Wyatt Tee Walker is perhaps best discovered through the stories of his life and the personal collection he and his wife created. We anticipate opening the collection for research use after processing is completed by the fall of 2018. Working on the collection of such an accomplished and esteemed person makes me proud to be an archivist and to be preserving lives and stories like Dr. Walker’s. I am honored for the opportunity to do this work, as the University of Richmond is honored to help preserve his significant legacy.