(Note: This post was authored by Taylor McNeilly, Processing & Reference Archivist.) Hello, and welcome to another edition of #WyattWalkerWednesday! For this week’s post, I want to talk about a portion of the Dr. and Mrs. Wyatt Tee Walker Collection that many may not even realize could exist — but is already getting attention: Dr. Walker’s work as an ethnomusicologist and composer.

Dr. Walker is, of course, primarily remembered for his work on the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ’60s, as well as his continued work in that vein throughout his life. He is also well remembered as a devout and active pastor, gaining a doctorate in theology from Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School in 1975 (while already having been senior pastor at Canaan Baptist Church of Christ for eight years or so, talk about busy). But how many of you know that his doctoral thesis for that degree focused on Black Gospel music and its role in the Civil Rights Movement?

Dr. Walker donated his copy of that thesis, entitled “Scaffold of Faith: The Role of Black Sacred Music in Social Change,” to the University of Richmond before his passing. It is one of multiple items in the collection linked to Dr. Walker’s active role in this field. His work as an ethnomusicologist studying Black Gospel music, its roots in American slavery, and its effects on the modern American music scene, would continue throughout his life. In 1976, he organized a “Gospel Picnic” for the Newport Jazz Festival, followed six years later by a “Festival of Black Gospel” in 1982. In 1994, he wrote an article published in Score Magazine entitled “Music is Ministry, As Preaching is Ministry.” This article focused on the role of traditional Black Gospel in the black church, as well as the contemporary shift away from traditional music and that trend’s destructive effects on black churches and their communities’ faith.

Throughout this time, Dr. Walker was also writing and publishing books that focused on the Black Gospel tradition. His work on some, such as the “African American Heritage Hymnal,” are widely known and used today in black churches. Others, including “Spirits that Dwell in Deep Woods: The Prayer and Praise Hymns of The Black Religious Experience,” catapulted Dr. Walker to international fame. In fact, an unpublished manuscript in the collection recounts how Dr. Walker was introduced to Hisashi Kajiwara, a Japanese minister who came to Canaan Baptist Church of Christ from Japan to study under Dr. Walker. The manuscript goes on to tell how Kajiwara also introduced Dr. Walker to a Japanese pop star who, being engaged to a Catholic woman, asked Dr. Walker to fly to Japan with a group of gospel singers and coordinate the wedding music. Kajiwara would also go on to work with the Kobe Mass Choir and the United Church of Christ in Japan to translate and publish some of Dr. Walker’s work, including “Spirits that Dwell in Deep Woods.”

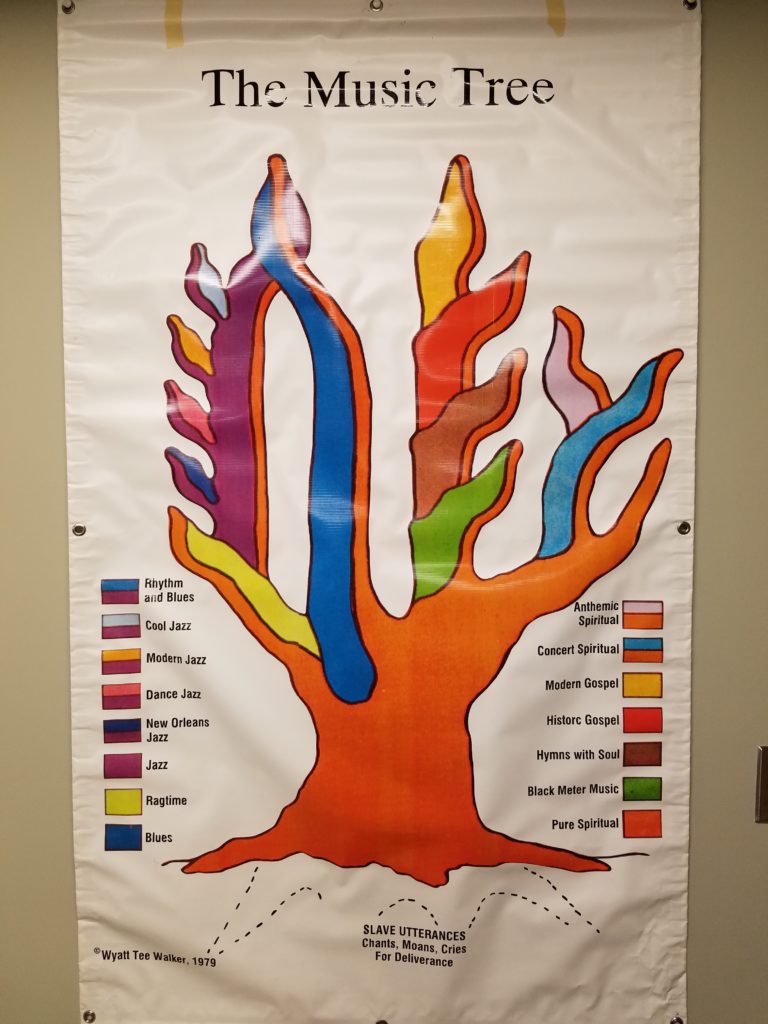

Perhaps the most visually stunning work on ethnomusicology that Dr. Walker donated is his large scale Music Tree poster, pictured above. This item, printed on canvas, is copyrighted 1979, four years after his Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School thesis. The poster is an image of a tree drawn by Dr. Walker depicting the growth of Black Gospel out of, at its roots, the “utterances and moans” of slaves brought to America. The trunk of the tree being Black Gospel, the branches — some intertwined — show the development of various forms of music both sacred and popular. The poster also seems to be accompanied by a VHS tape labeled “Roots of Music/Music Tree.” As I’ve previously mentioned, I’m currently focusing on processing the manuscript and object portions of the collection, so I can’t yet speak to the contents of the VHS. And since I’m not finished processing the manuscript materials yet, there may be even more material pertaining to Dr. Walker’s work with music waiting to be found, organized, and described. The ethnomusicology research potential in this collection is already exciting our faculty and researchers near and far, so I’m eager to finish the collection and open it to research, hopefully this fall.

And that’s it for this week’s post! As always, keep an eye on Boatwright Library’s Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter feeds to keep up with our activities both in RBSC and outside the division. Otherwise, I’ll be back next week with another #WyattWalkerWednesday post!

I’m so glad I googled this image! I’m using “Somebody’s Calling My Name” as part of doctoral thesis bibliography are Perkins School of Theology! I never knew this chart existed. I’m using the image with attribution to help people visualize his work.

On another note, my mother is a native Richmonder and an alum of Virginia Union! She and Dr. Walker were there at the same time!

(Ironically), just two days ago I referred attendees (at a workshop I led at Gordon College) to Dr. Walker’s book, “Somebody’s Calling My Name”, and its images of the historical timeline of Black sacred music; and the gospel tree pictured above. I first used this book during college in 1980 and have kept a copy in my library ever since.

Please note: Dr. Walker identified the trunk of the tree as the Pure Spiritual, not Black Gospel.