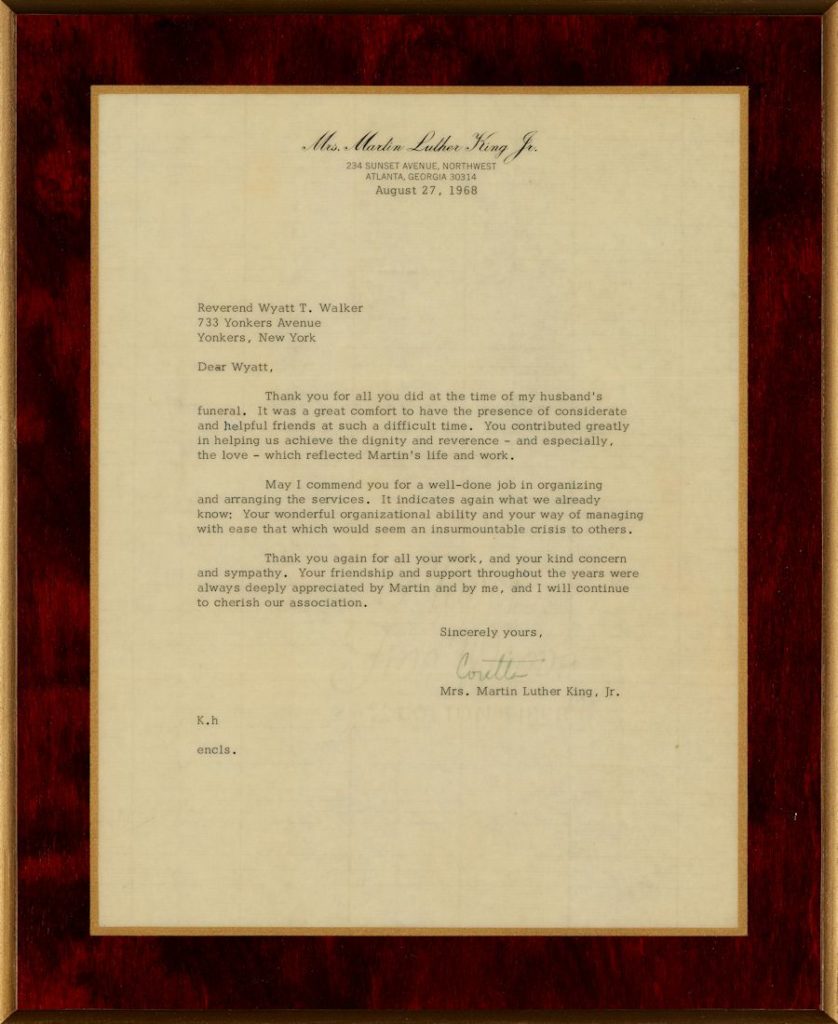

(Note: This post was authored by Taylor McNeilly, Processing & Reference Archivist.) Welcome back to the Something Uncommon blog with another #WyattWalkerWednesday post! This week, I want to let you all know about progress happening on some non-manuscript materials within the collection.

Now, if you’ve been keeping up with the posts concerning the Dr. and Mrs. Wyatt Tee Walker Collection, you may recall that I said we would be focusing first on the manuscript materials and turning attention towards the A/V (audiovisual) material later. This is partially to ensure that we can open the manuscript portion of the collection to researchers as quickly as possible, as processing manuscript materials can be done much faster than A/V materials. Let me talk about what A/V materials are – and why they’re so much harder to process – before telling you all the great news!

So A/V material, or audiovisual material, is a term used to refer to a whole host of different types of materials. These typically include audio recordings, video recordings, and still images. Each of these categories can take multiple forms, of course. Audio cassettes, vinyl recordings, even wax cylinders – these are all audio recordings, so they fall into the A/V material category. Similarly, video recordings can be on DVD, VHS, or film reels – the Walker Collection includes some 16mm film reels and a couple 8mm film reels as well. Photographs and other still images are perhaps the mostly widely varied – you have photographs, tin types, cyanotypes, various slides, photograph negatives, daguerreotypes, and so forth. There are archivists who specialize specifically in different types of A/V materials, because each format has its own preservation requirements, including what it should be housed in, what temperature the room should be kept at, and even if it can be viewed under different kinds of light.

The Walker Collection has a lot of different formats for A/V material. As I mentioned above, we have different formats of video recordings, and I’m sure I’ve mentioned before the 10,000 or so slides and countless photographs. Since I’m more of a generalist/digital archivist, I don’t have the level of expertise with A/V materials that would let me process these materials as quickly as manuscript material, so I’ve been working through the manuscript items first to let researchers have access faster. However, one thing that most archivists know immediately about A/V material is that it is almost never as stable as manuscript material.

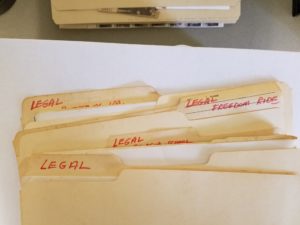

Another format we have plenty of is audio cassettes. In fact, our current inventory lists 780 audio cassettes, some dating from as early as the 1960s. While my predecessor and I have been processing the manuscript material for the collection, some of the student workers here at Boatwright Library created an inventory of the audio cassette tapes for us. This has allowed us to get quotes from various digitization vendors to move forward with this important work: the “life expectancy” (how long the recording will be accessible) for cassette tapes sits somewhere around 10-30 years, according to most estimates. This means that, in the case of the earliest of these recordings, we may already be too late – but we have to try. As such, we’ve begun moving forward on a digitization project with a large portion of the A/V materials, with the 700+ cassette tapes taking center stage.

All of this is very exciting, especially for the cassettes, film reels, and single reel-to-reel audio recording we have in the collection. Details on the project – and the eventual end result, digitized copies accessible to researchers who’d like to hear the sermons and speeches of Dr. Walker – will be forthcoming. The project is still in its early stages, but I’ll keep you all updated on this – as well as my progress processing the manuscript materials – as progress happens. So keep an eye on this space!